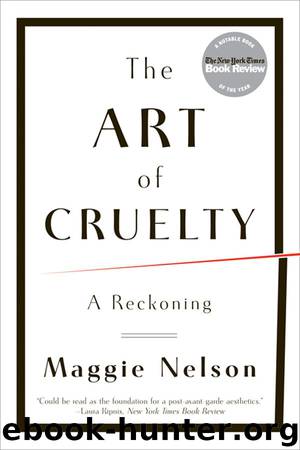

The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning by Maggie Nelson

Author:Maggie Nelson

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Publisher: W. W. Norton & Company

Published: 2011-07-10T22:00:00+00:00

WHO WE ARE

WITTGENSTEIN NEVER became what might properly be called a religious believer, despite his self-cajolements to the contrary (“Go on, believe!” he wrote in a note to himself around 1944. “It does no harm”). Nonetheless, he remained as prone to self-doubt and self-abasement as any serious Christian. (It was arguably this propensity that drove him toward Christianity, rather than toward his Jewish roots.) For in Christianity, to “know what you are” means facing the wretchedness of one’s original sin. In which case, the most correct apprehension of our situation on this swiftly tilting planet might be best summarized by the title of Jonathan Edwards’s famous 1741 sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

In this sermon, Edwards memorably describes the situation of all “natural men” (i.e., nonbelievers) as follows: “The wrath of God burns against them, their damnation does not slumber; the pit is prepared, the fire is now made ready, the furnace is now hot, ready to receive them; the flames do now rage and glow. The glittering sword is whet, and held over them, and the pit hath opened its mouth under them.” Speaking directly to the unredeemed, Edwards warns, “The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider or some loathsome insect over the fire, abhors you.” To know “what we are” is to know our essential unworthiness, and to believe that is only by the grace of God that we are not dropping, right now, into the pit prepared for us.

This portrait of the human soul contrasts starkly with the one presented by a certain banner I drove by for a period of time in 2007, one that hung over the entrance to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The banner read, in large block letters, “IN VIOLENCE WE FORGET WHO WE ARE.” I later learned that the quotation comes from writer Mary McCarthy, and was rendered into this banner by artist Barbara Kruger.

The intention behind the banner was, no doubt, virtuous. Nonetheless, every time I drove by I found myself in loose, if inchoate, disagreement. For many have argued precisely the opposite: that it is through violence that our souls come, as it were, into focus. Greek tragedy likes this idea; it is also a good description of our American mythos of regenerative violence. Sartre’s introduction to Frantz Fanon’s anticolonial classic The Wretched of the Earth sets forth something of the same—that it is through “irrepressible violence” that man “re-creates himself,” that “the wretched of the earth” finally “become men.” A well-known recruitment slogan for the U.S. Army underscores and expands the point, in its suggestion that to become a soldier is to “Be All That You Can Be.”

Had she not starved herself to death in solidarity with the French Resistance in the 1940s, and had she somehow ended up an exile in Los Angeles, an elderly Simone Weil might have nodded in agreement while driving by Kruger’s LACMA banner. For Weil’s famous 1940 essay,

Download

The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning by Maggie Nelson.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18629)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5475)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3677)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3543)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3529)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3451)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3360)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3324)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3178)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2918)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2918)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2883)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2725)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2719)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2670)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2640)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2587)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2579)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2510)